How Soil Health Directly Impacts Climate Change and Farm Sustainability

Posted on February 19, 2026

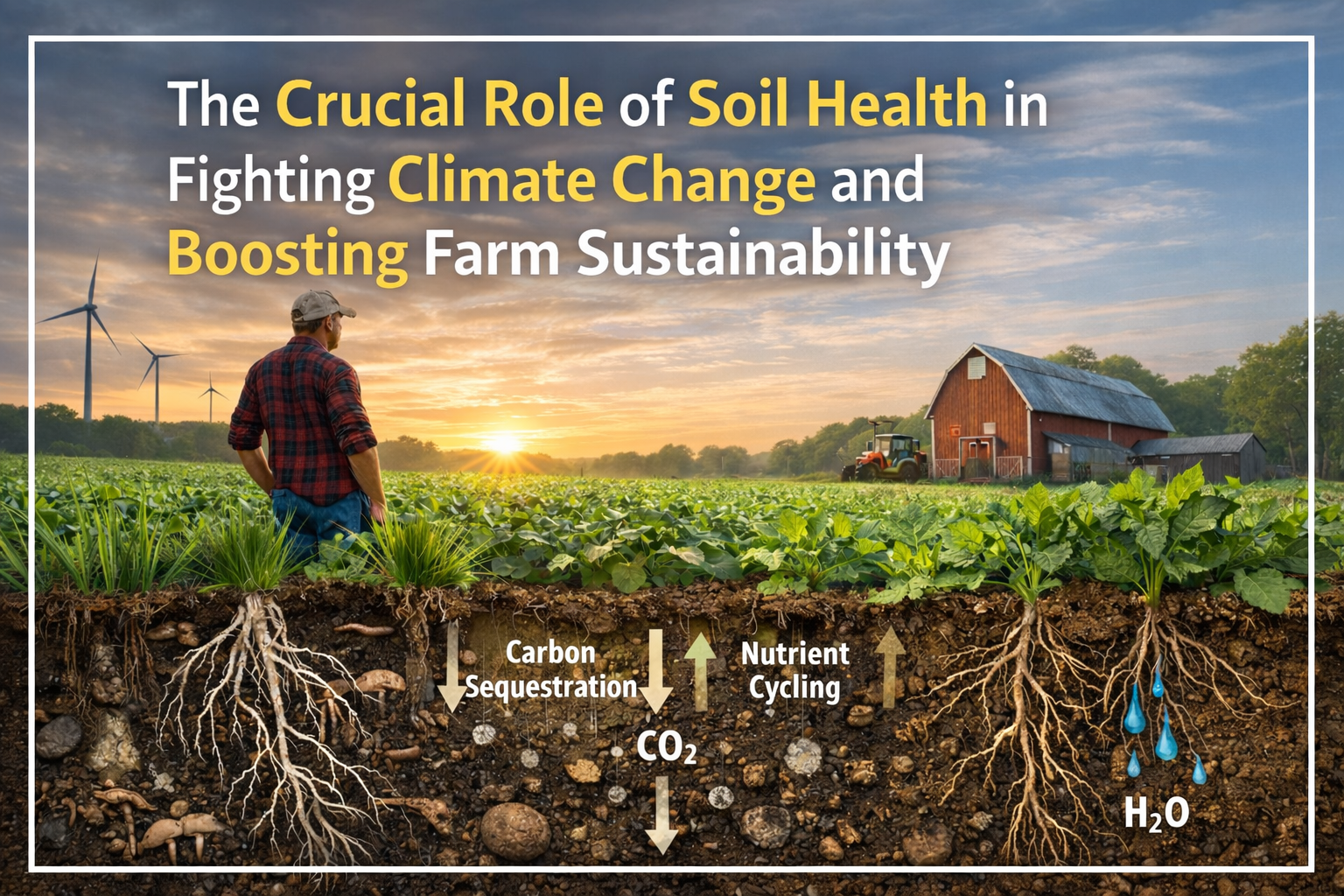

Soil health was initially considered a farm-level local issue, but now it has become a major point of climate concern worldwide. Soil is a natural habitat that contains minerals, organic matter, water, air, and a diverse range of living microorganisms. The ecosystem services of a healthy complex system not only help to stabilise the climate but also to maintain agricultural productivity.

Good soil is like a two, in, one product. It provides a great environment for plants to grow and, at the same time, it is a natural regulator of the carbon cycle, making it less vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. On the other hand, poor soils release the carbon they have stored, become overused and unbalanced in nutrients, and therefore, are more prone to weather extremes.

This kind of self-reinforcing cycle of soil health and climate adaptation has immediate effects on the global food system; thus, soil care should be regarded as the foundation of both sustainable farming and climate change strategies.

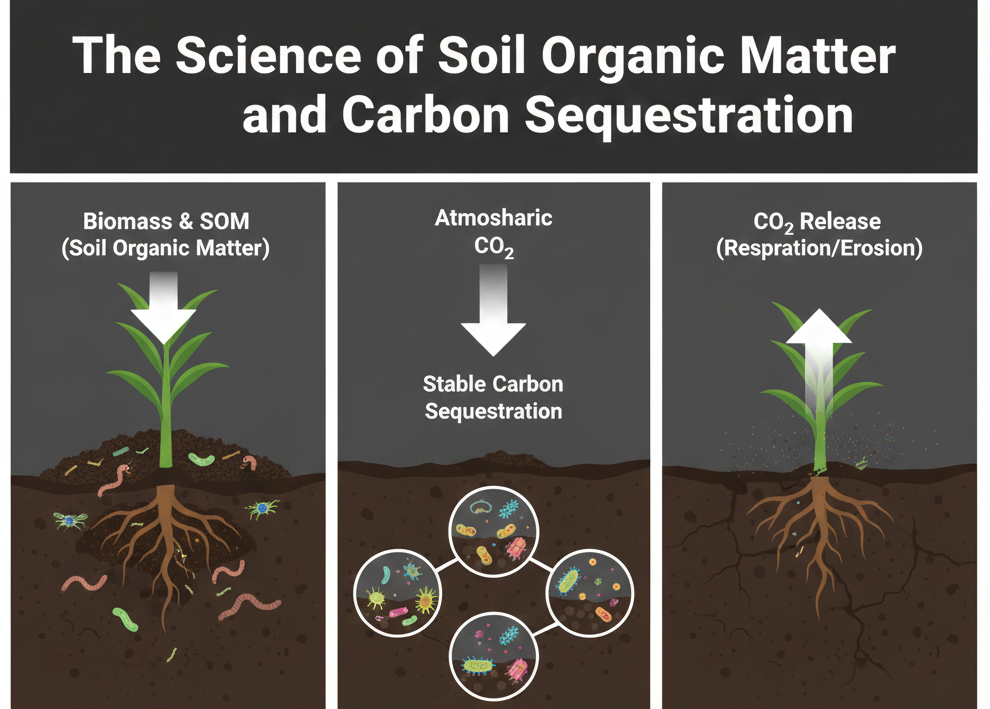

The Science of Soil Organic Matter and Carbon Sequestration

Soil organic matter (SOM) is essentially the main contributor to carbon storage in farm areas. It is composed of decomposed plant materials, root secretions, and microorganisms, and thus refers to the carbon pool in soil. As a large portion of SOM is carbon, soil is thus one of the largest terrestrial carbon reservoirs.

Worldwide, the top 1 meter of soil stores approximately 1,417 gigatonnes of carbon, nearly double the atmospheric pool, with deeper layers tripling this total to around 2,500 gigatonnes, exceeding the combined carbon in the atmosphere and all vegetation. This soil carbon reservoir capacity varies with soil texture, mineral composition, climate, and management practices, rather than remaining permanent. Stable organic matter, such as humus, persists for several decades, particularly when protected within soil aggregates that act as barriers to decomposition and mineralisation.

Soils with high aggregate stability and balanced C: N ratios retain carbon very well. Slight organic matter increments can, on the one hand, yield enormous climate benefits, and on the other hand, co-benefits such as improved fertility and structure.

Microbial Life and Greenhouse Gas Dynamics in Soil

Soil microbes control the majority of the greenhouse gases exchanged between the land and the atmosphere. Microbial respiration releases carbon dioxide as organic matter decomposes. Although it is a natural process, it speeds up when soils are disturbed or are overloaded with readily available nutrients.

Nitrous oxide emissions are very much dependent on microbial nitrification and denitrification. Agricultural soils account for more than 60% of global NO emissions, mostly due to excess nitrogen and poor aeration. Choosing a greenhouse can help regulate environmental factors and improve soil conditions, reducing the impact of emissions. In compacted or waterlogged soils, anaerobic pockets provide a habitat for denitrifying bacteria, thereby increasing emissions.

The production of methane in the soil is related to the presence of oxygen. Methane-producing organisms dominate the anaerobic soils, thus giving off methane, whereas methane-consuming bacteria reduce the emissions in well-aerated soils. Therefore, the physical condition of the soil and the management of its microbial biomass become very important for maintaining a balanced soil greenhouse gas (GHG) profile.

Farming Practices that Strengthen or Degrade Soil-Climate Function

Farm management is the main lever by which soil can be made a carbon sink rather than a carbon source. When intensive tillage breaks down aggregates, it exposes carbon that is otherwise protected and also increases erosion losses. After a while, this deteriorates the soil structure, and carbon is released more quickly.

On the other hand, regenerative as well as conservation-oriented practices contribute to soil function restoration. Long-term field experiments in different climatic zones demonstrated that these kinds of systems have the potential to raise soil carbon reserves by 0.3 to 1.0 tonnes per hectare per year, and at the same time, lower emission intensity per unit of yield.

Practices that consistently improve soil-climate performance include:

- – Reduced or no tillage to protect aggregates and microbial habitats

- – Cover crops and residue retention to maintain continuous organic inputs

- – Diverse crop rotations to stabilize nutrient cycling and soil biota

Conversely, excessive synthetic fertilizer use often increases degradation rates, elevates nitrous oxide emissions, and reduces microbial carbon efficiency.

Soil Structure and Water Retention in Climate Resilience

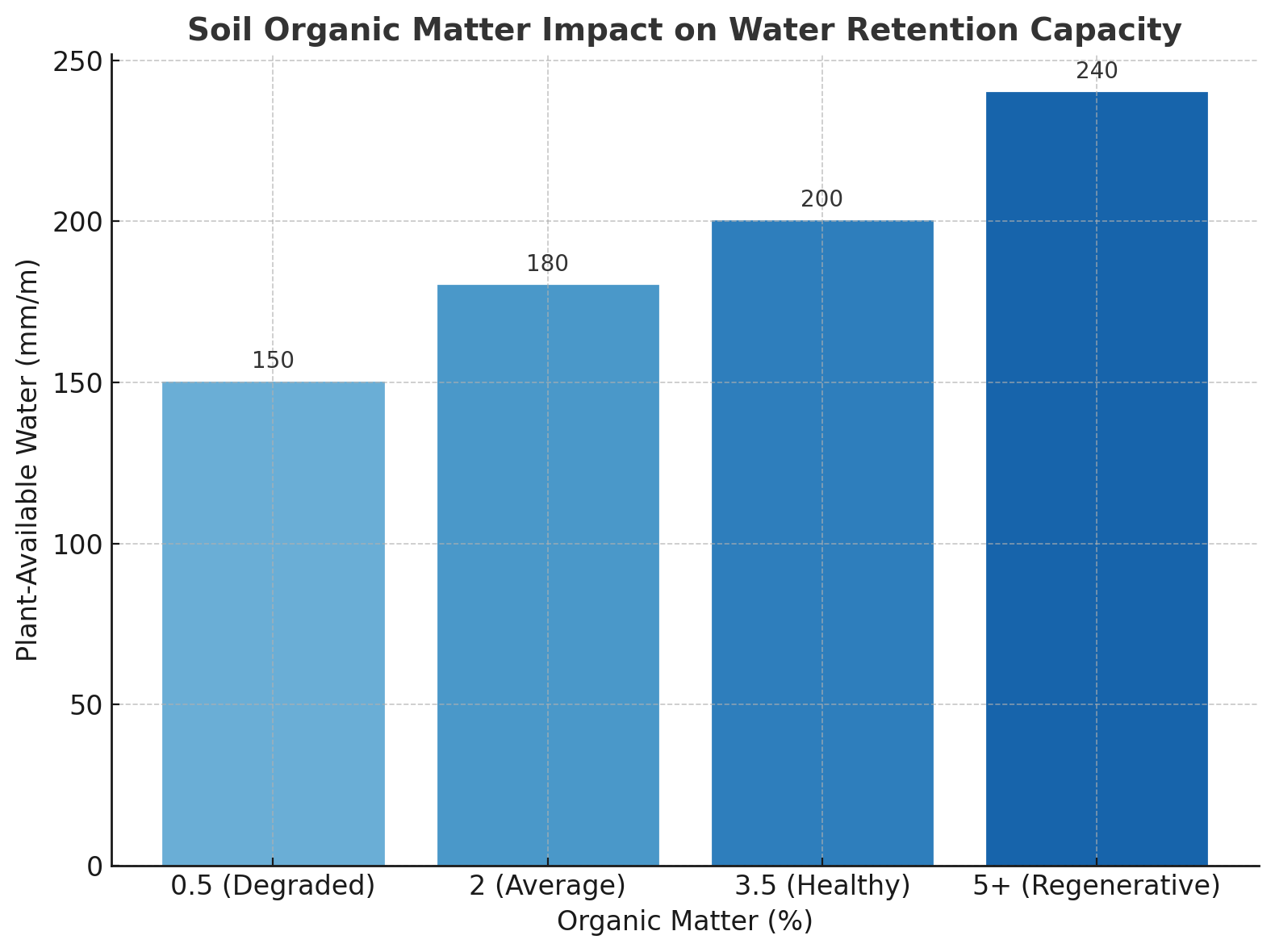

Soil structure is a major factor that determines how water can penetrate the soil, move within it, and be retained at different depths of the soil profile. In fact, well-aggregated soils with balanced porosity usually allow rainwater to infiltrate the soil rather than run off the surface, thus lowering erosion and the risk of flooding.

Studies have shown that soils with a higher content of organic matter can retain approximately 20% more water available to plants than those that are degraded. This enhanced capacity is clearly demonstrated below [chart], where increasing organic matter from 0.5% (degraded) to 5%+ (regenerative) boosts plant-available water from 150 mm/m to 240 mm/m. This additional water-holding capacity serves as a powerful mechanism for drought resistance, supplying water to crops during low rainfall periods while reducing evapotranspiration losses.

Climate variability is increasing, and soil hydrology is becoming even more important. Good quality soils are a buffer to both drought and excess rain, whereas compacted or degraded soils worsen the effects of climate by quickly losing water and drying out faster.

Soil Biodiversity as Ecosystem Insurance Against Climate Stress

Soil biodiversity plays a crucial role in maintaining soil functional stability under the impact of climate change. Earthworms, fungi, nematodes, bacteria, and many other soil organisms live and interact at different trophic levels within the soil food web. The large variety of organisms brings about redundancy, which means that important processes will continue to operate even when some species are lost.

Soils full of organisms have a greater capacity to withstand periods of heat and drought. The interactions of predator, prey, rhizosphere activities, and symbiotic associations are the major factors that shape the resilience of the ecosystem. Consequently, when biodiversity is lost, nutrient cycling is greatly simplified; thus, the ecosystem becomes more vulnerable to climate shocks and crop yields fluctuate. Hence, preserving soil biological health is critical not only for the provision of ecosystem services but also for the viability of farming systems in the long run.

Soil Amendments and Innovations in Climate-Mitigation

Soil amendments can significantly impact carbon dynamics when applied correctly. Biochar, a carbon-rich material obtained from pyrolysis, has recalcitrant carbon that is hardly decomposed and thus remains in the soil for a very long time. Additionally, it enhances cation exchange capacity and provides a microbial habitat.

Compost and green manures contain different organic molecules that contribute towards enhancing soil structure, increasing nutrients, absorbing capacity, and stimulating microbial activity. Meta-analyses reveal that the use of biochar may result in lowering nitrous oxide emissions by 10 to 30 percent, with the variation depending on soil type and general management.

New technologies like microbial inoculants and carbon-stabilising conditioners are very promising, but without proper agricultural practices, they are unlikely to bring the climate-positive effects that can be counted on. Online agricultural marketplaces like agribegri, provide a variety of soil health products and innovations for farmers wanting to implement these practices.

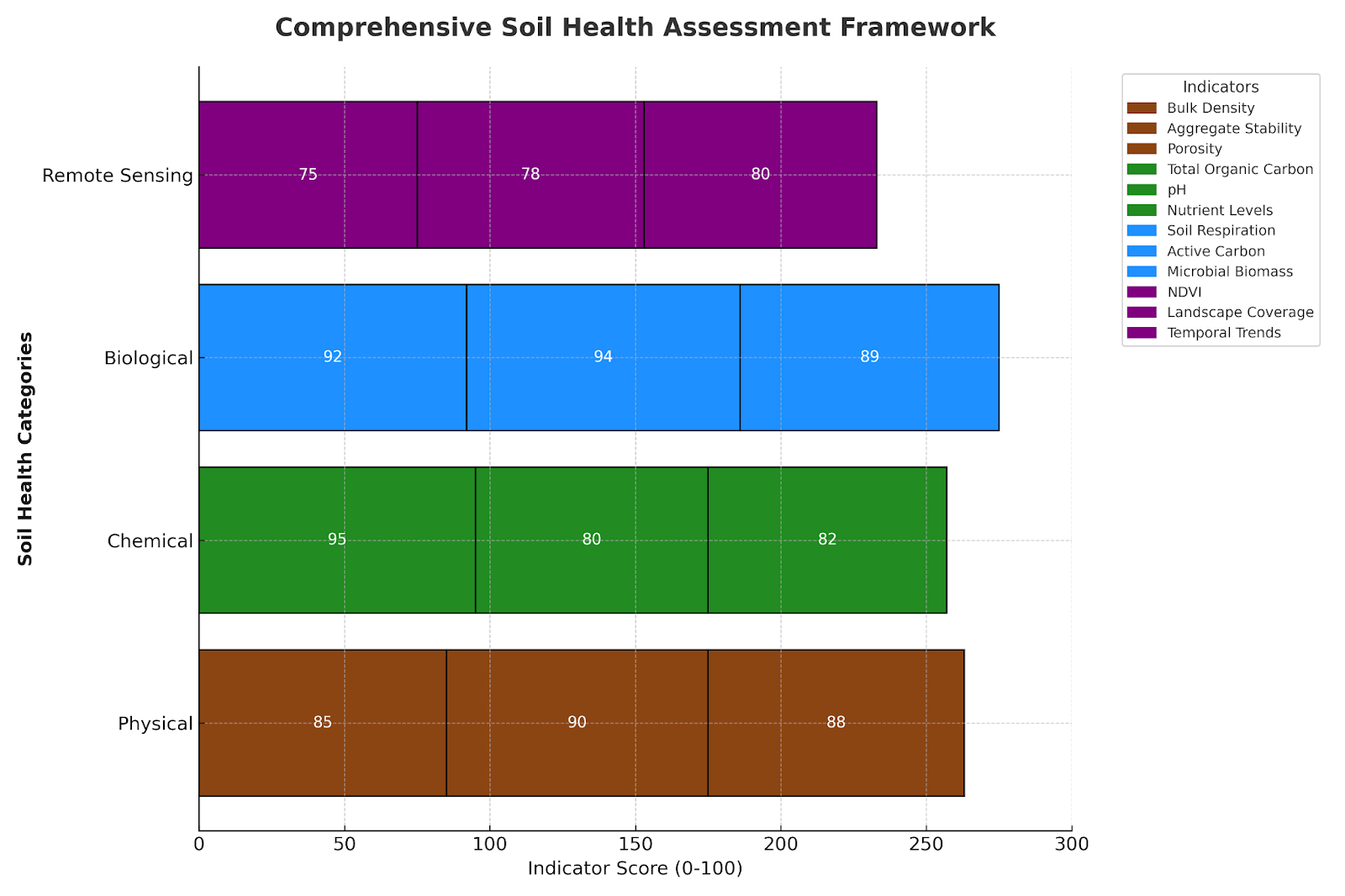

Measuring Soil Health for Climate Impact Assessment

Soil health measurement is crucial for linking management changes to climate outcomes. It is still beneficial to use traditional indicators like bulk density and total organic carbon. However, biological and structural metrics reveal more detailed information.

Contemporary evaluation mixes:

- – Soil respiration and active carbon tests

- – Aggregate stability and porosity measurements

- – Remote sensing for landscape-level monitoring

Correct soil metrics are the basis of carbon monitoring systems, on-site diagnostics, and new carbon credit verification frameworks.

Soil Health Policy, Incentives, and Global Initiatives

Policy and institutional support are key drivers of adoption. Farmers risk less financially when they invest in soil stewardship through programme endorsement. Major global soil projects have put soil on the agenda of climate change discussions, among them efforts by USDA NRCS, the EU Green Deal, and the 4 per 1000 Initiative.

These arrangements are usually aimed at fostering climate, smart agriculture, but still, questions remain, such as how complicated the process of verification is, whether the incentives are consistent, and how adaptable the region is.

Integrating Soil Health into Long-Term Farm Sustainability Strategies

Soil health is simultaneously the ecological basis and economic asset. Healthy soils increase input efficiency, make yields more stable, and reduce exposure to climate risk. Eventually, it means lower yield fluctuations, higher gross margins, and increased land value.

Farms that treat soil as a long-term asset rather than a consumable input will be better able to deal with the uncertainties of climate. The integration of soil care with sustainable practices will not only make farms more resilient but also help in climate change mitigation and food security at a global scale.